I spent nine years at Spotify leading design systems and accessibility. During that time, I learned as much from what failed as from what succeeded. I'm sharing these insights not to critique decisions made at the time, but because I believe they're valuable and can help others navigate similar challenges. This is the first in a series exploring those lessons.

A few years ago, I walked out of a particularly frustrating meeting discussing federated design systems and wrote down a title: "The Fallacy of Federated Design Systems." I never got around to writing the piece. Then Nathan Curtis published an article with that same title, and he nailed it.

Nathan's analysis of the myths surrounding the federated model, the way these systems are sold, and the false promises about distributed ownership and community contributions is spot on. He dismantles the theory brilliantly. But here's what I want to explore: what happens when organisations try to make federated work anyway? Not because they misunderstand the theory, but because the promises sound genuinely appealing.

During my nine years at Spotify, I watched the federated approach fail twice, in two different ways. I want to walk through what actually happened, where it broke down, and why the failures were so stark. Because knowing the theory is one thing. Living through the implementation is another.

The promise: distributed ownership

When everybody owns something, nobody owns it. - Milton Friedman

The federated model suggests that design system work can be distributed across multiple teams without a central authority. It sounds democratic. It sounds efficient. It sounds empowering. In practice, it creates an ownership vacuum.

Who's responsible for defining the architecture of the design system? Who establishes and evolves the processes needed to scale? Who ensures quality and consistency? Who maintains the infrastructure on which the system depends? Who deals with the unknown challenges that will inevitably occur?

In a federated model, the answer is often "anyone," which quickly becomes "nobody at all."

I've observed a pattern in organisations that pursue federated models. They tend to underestimate the value of experienced design system practitioners. This is particularly common in organisations that place greater emphasis on backend development, where the complexities of UI development and the effort required to operate design systems at scale are often oversimplified and undervalued.

What this looks like in practice

I've seen this play out twice at Spotify in a team focused on owning a specific part of the Spotify ecosystem, operating separately from the core design system.

The first attempt: Was a federated model with a small central team providing support, guidance, and frameworks. The promise was solid. In practice, the organisation struggled to understand the purpose and value of the central team, so they were treated as a free resource and constantly pulled into other projects. The promised support, guidance, and frameworks that would have made the system viable never happened. No one was accountable for the fundamentals. The basic work of operating a design system simply didn't happen because nobody was clearly responsible for doing it. Even when someone was responsible, they weren't given the time to do the work. The result was degraded sentiment towards design systems within that department.

The second attempt: When the first attempt ultimately failed, the organisation went even further. They disbanded the central team entirely and pursued a fully federated approach. No transition plan. Zero strategy beyond "teams will figure it out." The approach was even more hands-off than before. Again, no one was accountable for the fundamentals. Again, the basic work of operating a design system didn't happen. The result was the same chaos, just with even fewer guardrails.

Both times, the same pattern emerged: lack of clear ownership led to the same outcome. Neither attempt understood that operating a design system requires dedicated expertise and focus. Without it, the system collapses.

The promise: contributions from multiple teams

Our teams are already stretched. Pressure to deliver, meet deadlines, add new features, fix bugs, and address tech debt. When does a team actually have time to contribute a component to a shared system?

Creating a quality design system component isn't as simple as moving a feature implementation into a shared repository or Figma library. It requires real effort to ensure a component can scale to different use cases, meet accessibility and localisation requirements, and follow a consistent API that aligns with other components in the system. And that's just the component itself. You also need documentation, design-code alignment, and ongoing maintenance. These are specialisations.

Designing for reuse, scale, and consistency are skills that take time and experience to develop and require leadership. Feature teams aren't trained in this work, and frankly, they shouldn't have to be. Their expertise is in shipping features, not in building foundational systems and having the broad context required.

The federated model assumes that teams will find time for this work in addition to their existing commitments. They won't, and they don't.

What happened instead: duplication without reuse

The first attempt encouraged duplication with the promise of later consolidation. Engineers would copy and tweak code, creating new components regardless of how similar they were to existing ones. The system followed a defined naming strategy that enabled traceability; you could see exactly which components were created by which teams and where they were used. The idea behind this duplication-friendly approach was straightforward: prioritize speed by letting teams build exactly what they needed. The bet was that this autonomy would keep teams moving fast, and the central team would consolidate these duplicates later into single, reusable patterns.

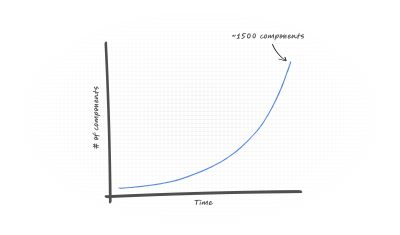

But it never happened. As we established previously, the centralized team wasn't given the time to do this work. The promised consolidation phase never occurred. As a result, the system only ever grew; it never contracted. At one point, it contained over 1,500 individual components.

The second attempt took a different approach. Teams were meant to create domain-specific components; the playback team would build the play button, the team responsible for search would build search components, and so on. Sounds logical.

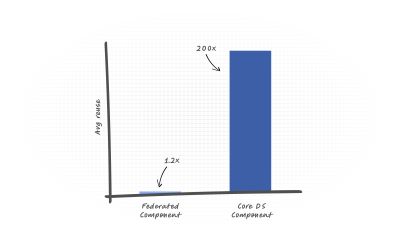

But there was no discovery mechanism. Teams couldn't find what already existed, so they built their own. The result? Average component reuse of 1.2 times per component, compared to 200 times for components from the centralised design system. Within 12 months, around 1,000 new components were created. Oh, and these didn’t replace the components from the first attempt; they were net-new things.

Both systems suffered from the same core problem. Teams built what they needed for their immediate use case. Without dedicated effort to consider reusability, make components discoverable, or consolidate similar patterns, you get exponential growth of barely reused components.

The ownership problem escalates

If Team A contributes a component and Team B needs changes to it, who is responsible for making those changes?

In the first attempt, owning teams pushed back on reuse. They didn't want the dependency. They didn't want to be responsible for supporting the needs of other teams in addition to their own work. The risk here is that you turn feature teams into pseudo-platform teams, now helping other people's problems alongside their existing commitments.

This tension is inherent to federated models. You're asking teams to take on platform responsibilities without giving them the focus, resources, or authority that platform teams need to be effective. And there's a deeper issue: platform work requires a different skill set entirely. It's about thinking systematically, how components interact, how patterns scale across use cases, rather than optimizing for a single product's needs. Feature teams are focused on solving problems perfectly for their context. Platform teams need to solve them adequately across many contexts. That's a fundamentally different mindset, and you can't just ask teams to switch between the two.

The promise: no need for a centralised team

This promise is fundamentally about money. The federated model gets framed as a way to get a design system "for free." You can save the cost of staffing a dedicated team by distributing the work across existing teams.

This thinking is both naive and demonstrates a significant misunderstanding of what's required to build and maintain a design system at scale. This thinking also tends to emanate from those in leadership positions, often abstracted away from the details and nuances of running a design system.

What actually happens without dedicated ownership

Both of Spotify’s attempts at federated struggled with the same fundamental problems that require dedicated ownership to solve.

The discovery problem: The first attempt had a basic discovery mechanism, but it was inadequate and went unused. The second attempt didn't bother building one at all - no tooling, no strategy. In both cases, teams couldn't find what existed, so they built their own. This isn't surprising - effective discovery requires dedicated effort and investment.

The quality problem: Who ensures components meet accessibility standards? Who maintains consistency in API design across the system? Who handles the unglamorous work of deprecation and migration? In both examples, nobody. These concerns simply weren't addressed because no one was clearly responsible for them.

The infrastructure problem: The first attempt wrapped components in a framework that required ongoing maintenance. The second attempt bundled UI, behaviour, and instrumentation into complex components that needed dedicated support. Both required significant infrastructure that the feature teams needed to maintain alongside their primary work.

The real cost

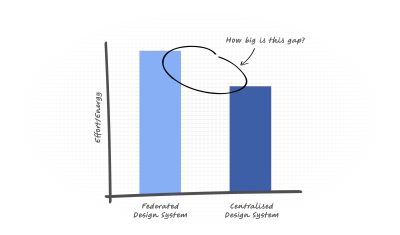

At scale, the effort required to support a federated model often exceeds that of a centralised one. You're just spreading that cost across multiple teams who are less equipped to handle it, and you're paying the overhead of poor coordination on top.

The second attempt is particularly revealing because it illustrates what happens when the necessary investment is not made. The previous central team was disbanded with no transition plan, and there was zero strategy for component discovery. No tooling or processes. Reuse was positioned as the goal, but nothing was built to actually enable it. Without the infrastructure to support distributed ownership, teams defaulted to what they knew: building their own solutions.

The design-engineering divide: why federated can't solve it

One consistent failure across both attempts was the persistent divide between design and engineering, a problem that federated models struggle to solve and often exacerbate.

The first attempt created a fundamental mismatch. Designers in the central team operated like a traditional centralized design system, creating a shared Figma library of components. But the engineering side was federated. This meant designers had centralized resources and shared components, but engineers lacked code implementations that matched what designers were sharing. There was immediate friction.

The second attempt didn't solve this. By removing the central team entirely and making no consideration for design alignment, the divide got worse. The first attempt had design components with no code implementations. The second created code implementations with no mapping back to design. Both ended up in the same place: misalignment.

The core issue is that aligned design and code require more than effort and collaboration; they require a shared understanding that parity between the two is non-negotiable. A federated model distributes this work across feature teams, but no single team sees the full picture or thinks holistically about the system. Each team focuses on its own slice of the experience in isolation. Patterns diverge. What designers expect doesn't match what engineers build. You end up with multiple implementations of the same design pattern, each slightly different.

This challenge is hard enough with a dedicated team working closely together. Without one, it becomes nearly impossible.

This is why, within Encore, we made parity between design and code non-negotiable. Our engineers were in Figma, and our designers were in code. No handoffs. Designs weren't thrown over the fence. This type of alignment necessitates a cultural shift, a fundamental change in how teams collaborate. In a small, centralized team, you can implement that relatively easily. But to scale it across an entire organization the size of Spotify? That's where federated models hit a wall. You can't mandate culture change across hundreds of autonomous teams.

When might federated actually work?

Despite what I observed at Spotify, I can see scenarios where federated might make sense, but they're genuinely rare and require specific preconditions most organisations don't have.

So what would you actually need?

Organisational infrastructure:

- Clear governance frameworks that multiple teams actually follow, not just document

- A strong cross-disciplinary collaborative culture - no silos

- An investment in the appropriate discovery tooling to allow teams to find and reuse what exists

- Processes that prevent fragmentation

- Accountability structures for quality standards

- Dedicated programme management to coordinate across teams

The right conditions:

- A mature design system practice that already exists in the organisation

- A scale that's small enough to keep coordination overhead manageable

- Multiple teams that genuinely have overlapping needs, who benefit from shared ownership

- Teams with dedicated capacity beyond feature delivery to invest in platform work

- A culture deeply rooted in distributed, collaborative thinking (organisations with strong open-source traditions sometimes have this naturally)

Most organisations don't have these things in place, and building them requires significant overhead. At that point, you're spending the effort anyway, just in a more complicated way.

Here's what I keep coming back to: at the point where you've invested enough time and energy to make federated work properly, would that same investment have been better spent on a well-run centralised team?

What does a centralised model require? A dedicated team. Clear ownership. Processes.

The complexity is lower, the coordination overhead is smaller, the accountability is clearer, and you can show value faster.

In most cases, the answer is obvious. The centralised model is more straightforward. You can always evolve towards more distributed contribution patterns later, once you have solid foundations in place.

Starting with federated means you're trying to solve the most complex organisational challenges before you've solved the fundamental design system problems.

The hard truth

Federated design systems aren't inherently bad, but they're significantly more challenging than they appear, and how they're sold. The promises sound brilliant. Who wouldn't want distributed ownership and community contributions? But delivering on those promises requires massive organisational investment that most teams hugely underestimate.

Both attempts at Spotify had smart people working on them. Neither was doomed from the start. But both underestimated what was required to make federated work at scale.

The first attempt had a small central team, but they operated within an organisation that didn't share their view on what their design system should be or how much investment it required. They were treated as a free resource rather than being given the authority and focus they needed. The second attempt removed central coordination entirely, betting that domain expertise and autonomy would solve the problem better than centralisation could.

Both attempts reflected genuine disagreements about priorities and trade-offs. But both created the same outcome: exponential growth in barely reused components, accumulated technical debt, and confusion about what the system was intended to provide. Crucially, this damaged the reputation of design systems as a concept, particularly amongst senior leadership.

If you're considering a federated model, ask yourself honestly: Do you have the culture, discipline, tooling, and governance in place to make this work? If not, are you prepared to build all of that infrastructure before seeing any value from your design system? Would that same investment deliver better results if put towards a centralised team that can start showing value much sooner?

A well-run centralised team delivers value faster, with lower coordination overhead and clearer accountability. Nathan Curtis was right that federated is a facet, not a model. What I've learned from watching it fail twice is how much damage these attempts do beyond just the immediate system. They poison the well, making it harder to secure investment for any future design system work. That's why starting with a solid centralised foundation matters - it builds trust and proves value, giving you the credibility to evolve towards more distributed patterns later.

Design systems are already challenging. Don't make them harder than they need to be.

Thank you to those in the Redwood community who helped to review and offering feedback on this article. 💜